The Three Waves of Mountain Destruction

“History never really says goodbye.

History says, ‘See you later.’”

— Eduardo Galeano, poet and writer

Often enough, but not every day, a time comes to stand up for something other than a second cup of coffee, one more helping of dessert: A time to step outside ourselves and work in common for something greater than our individual appetites. This is one of those times.

It’s hard, especially when mega-corporations promise to pay down your property taxes. It’s hard when they offer to give you, a registered voter, $900 a year or more into the future if the vote is in favor of a project. It’s hard to say no.

The Three Waves of Mountain Destruction

“History never really says goodbye.

History says, ‘See you later.’”

— Eduardo Galeano, poet and writer

Often enough, but not every day, a time comes to stand up for something other than a second cup of coffee, one more helping of dessert: A time to step outside ourselves and work in common for something greater than our individual appetites. This is one of those times.

It’s hard, especially when mega-corporations promise to pay down your property taxes. It’s hard when they offer to give you, a registered voter, $900 a year or more into the future if the vote is in favor of a project. It’s hard to say no.

Perhaps that’s why it is so much easier to say yes, or do nothing to oppose the plundering, as the sad legacy of the Green Mountains demonstrates. Since early colonial times, two historic waves of human destruction have battered the mountains, each crest followed by a brief trough of recovery. With a new swell rising — mountaintop industrial wind — Vermonters may have a last, best opportunity to prevent a third wave of devastation.

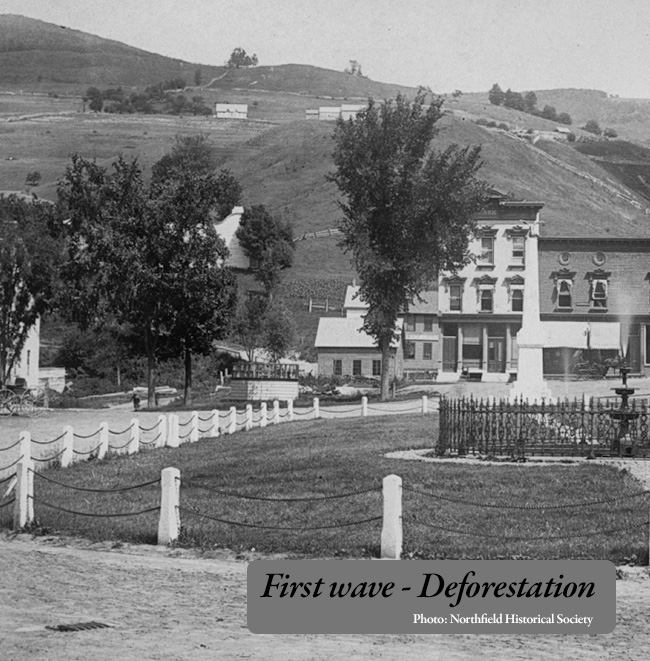

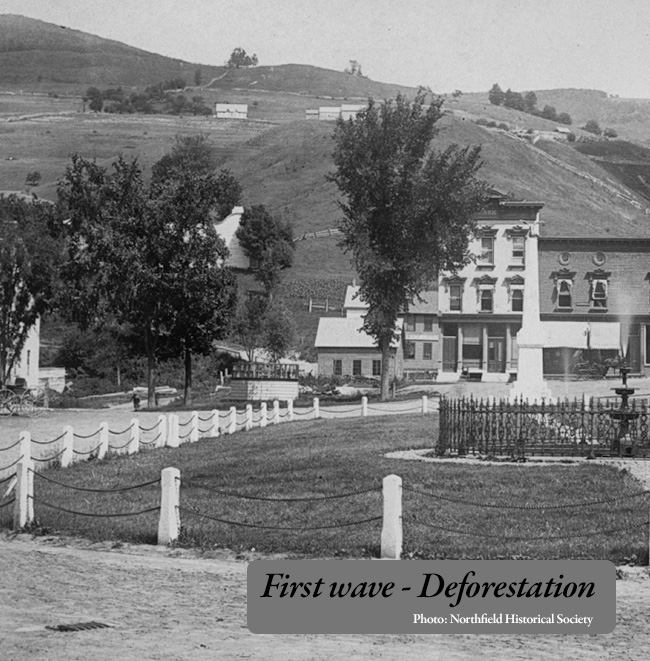

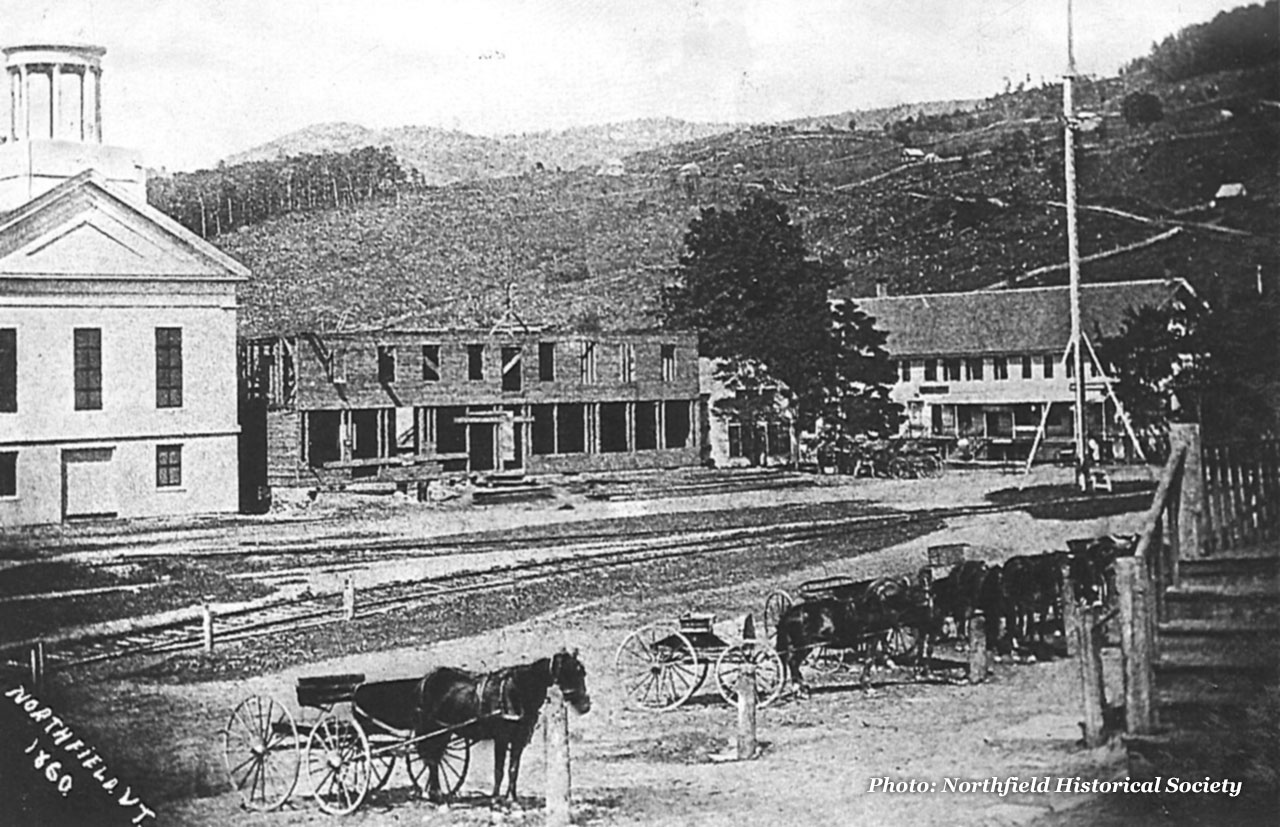

Vermont’s early settlers must have viewed the resources of the Green Mountains as inexhaustible. Having trekked north with land hunger in their bellies, they discovered what historian Lewis Stilwell called a “whole aristocracy of hardwoods” — oak, maple, beech, birch and ash — to be vanquished by axe and by fire.

Word spread down country: A hard man could hack a living out of the forests of Vermont. People came, they survived, and their numbers grew. In 1781, an estimated 30,000 lived in the Republic of Vermont. By 1791, 85,000, by 1800, 154,000; and by 1810, 217,000. These were “the Good Years,” when the land seemed lush and limitless, bountiful and boundless. Land values rose. Money was made. And, beyond the next hill, there was always more.

Perhaps that’s why it is so much easier to say yes, or do nothing to oppose the plundering, as the sad legacy of the Green Mountains demonstrates. Since early colonial times, two historic waves of human destruction have battered the mountains, each crest followed by a brief trough of recovery. With a new swell rising — mountaintop industrial wind — Vermonters may have a last, best opportunity to prevent a third wave of devastation.

Vermont’s early settlers must have viewed the resources of the Green Mountains as inexhaustible. Having trekked north with land hunger in their bellies, they discovered what historian Lewis Stilwell called a “whole aristocracy of hardwoods” — oak, maple, beech, birch and ash — to be vanquished by axe and by fire.

Word spread down country: A hard man could hack a living out of the forests of Vermont. People came, they survived, and their numbers grew. In 1781, an estimated 30,000 lived in the Republic of Vermont. By 1791, 85,000, by 1800, 154,000; and by 1810, 217,000. These were “the Good Years,” when the land seemed lush and limitless, bountiful and boundless. Land values rose. Money was made. And, beyond the next hill, there was always more.

“More” ran out. By the mid-19th century, our forests were eradicated for lumber and “pasturized” by sheep. In 1963, U.S. Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall, reflecting on the aftermath in The Quiet Crisis, his seminal book on conservation, wrote, “Not even in the cotton and tobacco belt were soils exhausted faster and forests mangled more thoroughly than on the hillsides of Vermont.” The first wave.

Vermont then entered the Great Twilight, a period of exodus for some and stagnation for many. Even as a new century of promise dawned – the twentieth – the 1912 Governor’s Commission on the Preservation of Natural Resources painted a dark portrait: “Our forests by reason of mismanagement are so rapidly disappearing… If we continue our present method or lack of method in dealing with them we shall in another fifty years have few forests on which to place a value.”

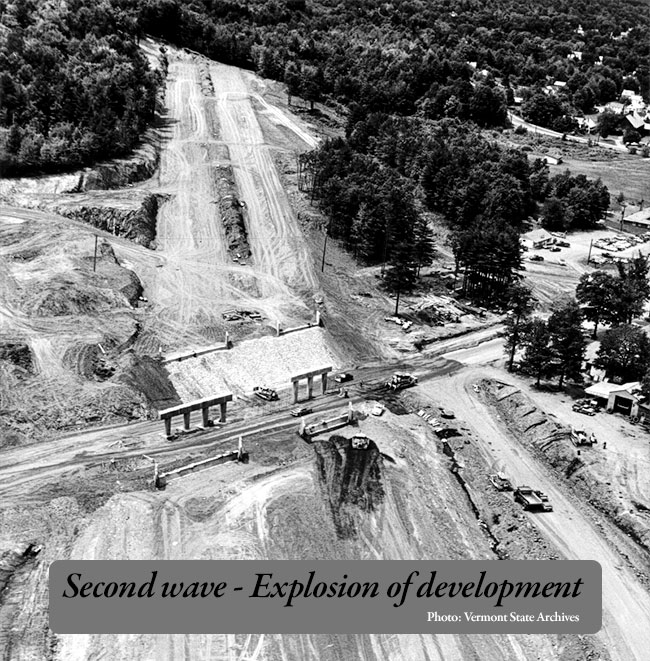

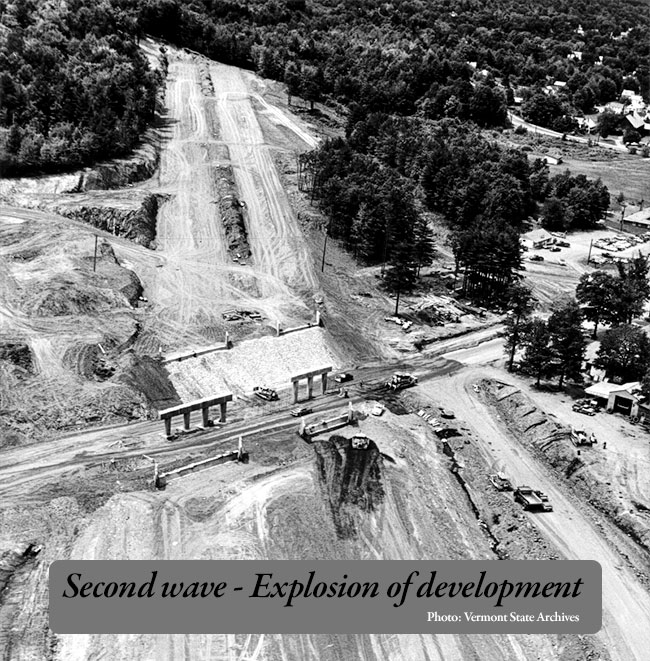

Eventually, we had little choice. Like addicts, we had to face up to our destructive behaviors or continue to decline and deteriorate. The 1960s were a wake-up call as the interstate highways uncoiled across the land. In 1961, Walter Schoenknecht, president of Mount Snow, bizarrely – but quietly – petitioned the Atomic Energy Commission to detonate an atomic bomb to create steeper ski trails. In 1966, lumber giant Weyerhaeuser used relatively more modest munitions to dynamite a wedge thirty-feet deep into Jay Peak’s summit for the tram house, a disfiguration that lingers.

Shocked Vermonters agitated for change. Walter Hard, Jr., the legendary editor of Vermont Life, asked plaintively “Shall Her Mountains Die?” His colleague Samuel Ogden, mourning “our mountain peaks … scarred with the worm-tracks of ski areas,” posed an environmentally existential question, “How long can we proceed along these easy ways before we do become ruined?”

In 1969, Governor Deane Davis’ Commission on the Environment set the stage for reform and rescue, calling for “a comprehensive approach … to assure development without destruction.” The next year, Act 250 became our Holy Grail, the first among equals of our many environmental laws, but it was quickly weakened once resistance grew. The second wave.

Today, we look back on those bad old days not imagining it could happen again.

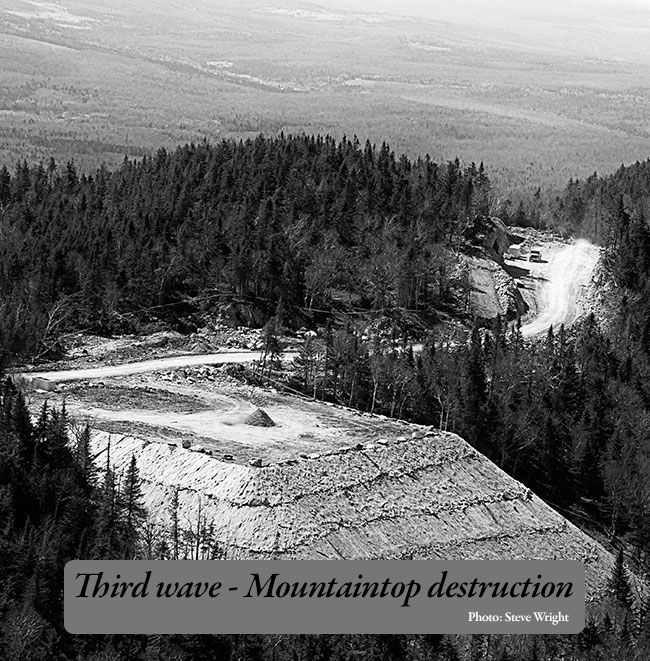

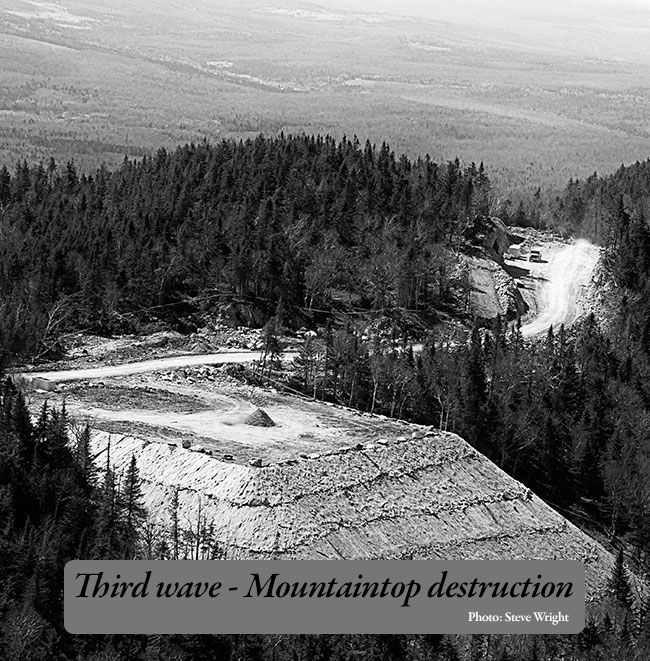

Now, in the early 21st century, a third wave is lapping at our summits and ridges. Our ridgelines are targets for 200 miles or more of blasting, bulldozing and road building for industrial wind developments. Unfortunately, many wind proponents, including a fair share of Vermont’s major environmental organizations, rationalize this ruin, arguing that Vermont must destroy its mountains in order to save them. They employ environmental relativism, justifying skinning our mountaintops for wind because West Virginia disembowels its mountains for coal.

It is time to stop, to reflect on our legacy of devastation and to determine our future. It is time to answer Walter Hard’s question, “Shall her mountains die?” It is time to ask, despite our pretensions of environmental virtue, if mountain destruction is simply and sadly part of Vermont’s DNA. It is, undeniably, time to take a stand against the third wave.

Eventually, we had little choice. Like addicts, we had to face up to our destructive behaviors or continue to decline and deteriorate. The 1960s were a wake-up call as the interstate highways uncoiled across the land. In 1961, Walter Schoenknecht, president of Mount Snow, bizarrely – but quietly – petitioned the Atomic Energy Commission to detonate an atomic bomb to create steeper ski trails. In 1966, lumber giant Weyerhaeuser used relatively more modest munitions to dynamite a wedge thirty-feet deep into Jay Peak’s summit for the tram house, a disfiguration that lingers.

Shocked Vermonters agitated for change. Walter Hard, Jr., the legendary editor of Vermont Life, asked plaintively “Shall Her Mountains Die?” His colleague Samuel Ogden, mourning “our mountain peaks … scarred with the worm-tracks of ski areas,” posed an environmentally existential question, “How long can we proceed along these easy ways before we do become ruined?”

In 1969, Governor Deane Davis’ Commission on the Environment set the stage for reform and rescue, calling for “a comprehensive approach … to assure development without destruction.” The next year, Act 250 became our Holy Grail, the first among equals of our many environmental laws, but it was quickly weakened once resistance grew. The second wave.

Today, we look back on those bad old days not imagining it could happen again.

Now, in the early 21st century, a third wave is lapping at our summits and ridges. Our ridgelines are targets for 200 miles or more of blasting, bulldozing and road building for industrial wind developments. Unfortunately, many wind proponents, including a fair share of Vermont’s major environmental organizations, rationalize this ruin, arguing that Vermont must destroy its mountains in order to save them. They employ environmental relativism, justifying skinning our mountaintops for wind because West Virginia disembowels its mountains for coal.

It is time to stop, to reflect on our legacy of devastation and to determine our future. It is time to answer Walter Hard’s question, “Shall her mountains die?” It is time to ask, despite our pretensions of environmental virtue, if mountain destruction is simply and sadly part of Vermont’s DNA. It is, undeniably, time to take a stand against the third wave.

Blasting and excavating I-91, Fairlee, Vermont. Photo: Vermont State Archives.

Eventually, we had little choice. Like addicts, we had to face up to our destructive behaviors or continue to decline and deteriorate. The 1960s were a wake-up call as the interstate highways uncoiled across the land. In 1961, Walter Schoenknecht, president of Mount Snow, bizarrely – but quietly – petitioned the Atomic Energy Commission to detonate an atomic bomb to create steeper ski trails. In 1966, lumber giant Weyerhaeuser used relatively more modest munitions to dynamite a wedge thirty-feet deep into Jay Peak’s summit for the tram house, a disfiguration that lingers.

Shocked Vermonters agitated for change. Walter Hard, Jr., the legendary editor of Vermont Life, asked plaintively “Shall Her Mountains Die?” His colleague Samuel Ogden, mourning “our mountain peaks … scarred with the worm-tracks of ski areas,” posed an environmentally existential question, “How long can we proceed along these easy ways before we do become ruined?”

In 1969, Governor Deane Davis’ Commission on the Environment set the stage for reform and rescue, calling for “a comprehensive approach … to assure development without destruction.” The next year, Act 250 became our Holy Grail, the first among equals of our many environmental laws, but it was quickly weakened once resistance grew. The second wave.

Today, we look back on those bad old days not imagining it could happen again.

Now, in the early 21st century, a third wave is lapping at our summits and ridges. Our ridgelines are targets for 200 miles or more of blasting, bulldozing and road building for industrial wind developments. Unfortunately, many wind proponents, including a fair share of Vermont’s major environmental organizations, rationalize this ruin, arguing that Vermont must destroy its mountains in order to save them. They employ environmental relativism, justifying skinning our mountaintops for wind because West Virginia disembowels its mountains for coal.

It is time to stop, to reflect on our legacy of devastation and to determine our future. It is time to answer Walter Hard’s question, “Shall her mountains die?” It is time to ask, despite our pretensions of environmental virtue, if mountain destruction is simply and sadly part of Vermont’s DNA. It is, undeniably, time to take a stand against the third wave.